By: Selina Li

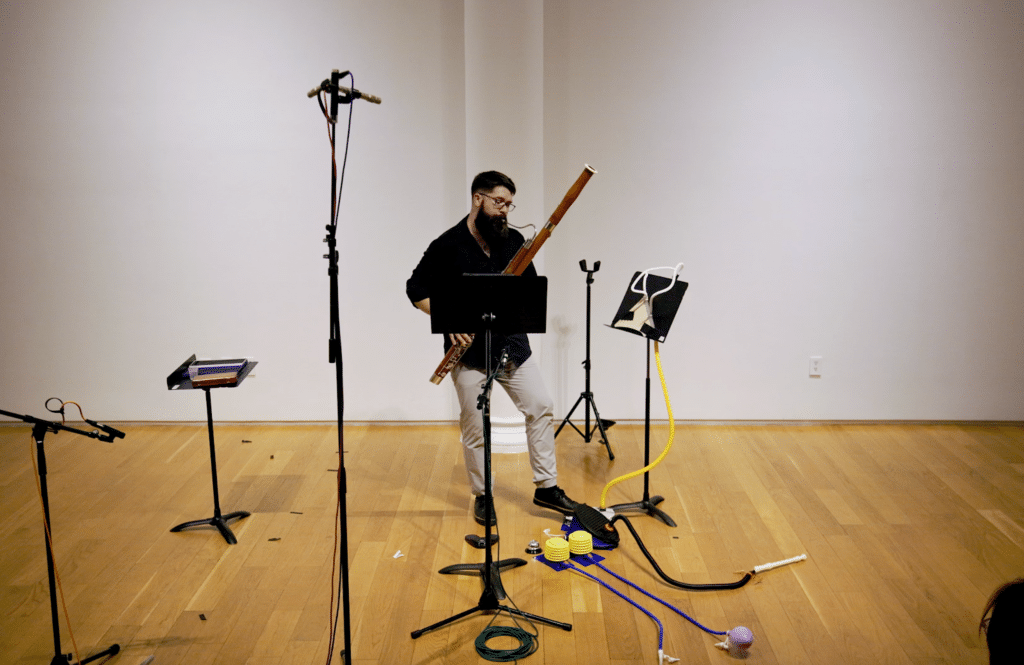

New York-based composer Yue Chen premiered her latest experimental piece last week, Pinocchio’s Nose, as part of the New Sounds New Sounds New series at Tenri Cultural Institute NYC. The piece has unique instrumentation and expressive themes, exploring traces of truth and lies. The piece is centered around the bassoon and incorporates a variety of woodwind instruments connected through air paddles, such as the recorder and Pai Xiao, along with props like balloons and a service bell. Chen, also known as Chen Shuhe Yue explains, “Air always leaves traces in its path, and so do lies.”

The work was performed by renowned bassoonist Ben Roidl-Ward, currently an Assistant Professor of Bassoon at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and recognized by The Washington Post as one of the “23 Artists Changing the Sound of Classical Music.” Roidl-Ward’s rich expressiveness and skill brought Chen’s narrative to life, vividly showcasing the depth of her musical storytelling. Roidl-Ward states, “The piece requires a whimsical, multi-faceted virtuosity from the performer, which was a challenge that I enjoyed both in the preparation and performance of the piece. The relationship between the bassoon and the other instruments, which sometimes work in tandem, other times in conversation, and other times in conflict, is the most exciting element of the piece to me. On top of that, there is the theatrical, sometimes satirical, effect of the music and the concept of the score itself.”

Photo Courtesy: Yue Chen / Ben Roidl-Ward playing the Bassoon for Yue Chen’s piece Pinocchio’s Nose at Tenri Cultural Institute NYC

The work was composed for the bassoon, an instrument commonly used in orchestra and chamber settings but with potential to be explored more as a solo instrument. “The bassoon’s complex structure provides extensive potential for exploration,” Chen says. “Alongside conventional playing, I used extended techniques to create a richer sound palette, including air sounds, key clicks, and timbre trills.” Chen also incorporated various timbral effects and vocal techniques, such as tongue clicks and lip sounds, to reflect Pinocchio’s voice when it tried to speak.

The Pai Xiao, a Chinese wind instrument, is a type of pan flute, with sounds imitating bird calls and human speech, symbolizing the lingering effects of lies. While playing, the performer uses one hand to manipulate a movable plastic tube on the Pai Xiao, representing an internal debate through a physical dialogue between his hands and mouth.

Photo Courtesy: Yue Chen / Ben Roidl-Ward (Left) and Yue Chen (Right) rehearsing

The piece opens with a dual identity represented by a simultaneous sound from the bassoon and recorder. The bassoon, using the overblow technique (which produces multiple pitches through increased air pressure), and the recorder, receiving maximum airflow through the pedal, together emit a piercing tone. These instruments symbolize both Pinocchio himself and the shadow of the father’s lost son. Throughout the work, there are repeated dual screams, each representing this twofold voice.

Chen drew inspiration from the story of Pinocchio and a film adaptation. In the film, a grieving father sees Pinocchio, the wooden puppet, as his child to escape his pain. To please his “father,” Pinocchio tries to transform into a real person. Both characters, though acting out of love, create a shared lie, ultimately facing the need to confront the truth.

Pinocchio’s image permeates the structure of the piece, as he clumsily and awkwardly tries to imitate human behaviors, moving from a rigid piece of wood to an almost-real figure. The music is not written with a strict rhythmic structure, only a few moments of regulated rhythm symbolizing societal rules, interspersed with fragments of spoken sounds representing Pinocchio’s struggle to communicate like a human. In this process, he learns to speak and pronounce human sounds, though imperfectly. The piece also includes sounds generated by physical actions, such as stomping on the floor. Repeated service bell chimes signify Pinocchio’s effort to restart each time he fails, like a reset.

As the piece progresses, the performer begins to press the balloon pedal, symbolizing Pinocchio’s naive approach to lying, unaware of right or wrong, he lies to please his father, despite not being his real child. Each time the balloons inflate represents a lie, with the long balloons metaphorically mirroring Pinocchio’s nose. Each inflation leaves an impression, symbolizing how lies, though often forgiven, leave traces like air.

Photo Courtesy: Yue Chen / Yue Chen setting up the stage for the Premiere of Pinocchio’s Nose

The work concludes with an open ending: the performer may choose to pop the balloons, signifying the self-destructive nature of endless lies, or leave them intact, suggesting a potential for a new beginning. Chen has woven sound and narrative with precision and logic. Chen elaborated, “Lies aren’t necessarily black or white. Pinocchio’s lies are rooted in a desire for his father’s affection; they are well-intentioned. Regardless of intent, all lies leave a trace, and one must stay true to oneself.”

“Since this piece calls for simultaneous engagement of a number of other instruments in addition to the bassoon itself, there was a great deal of logistical coordination and practice that stretched my multi-tasking abilities.” Says Roidl-Ward, “ I felt this was the perfect way to end the concert. As the balloon inflated more and more towards the end, I saw several members of the audience cover their ears in anticipation of the inevitable pop.”

Yue Chen is currently pursuing a Doctor of Musical Arts degree in composition at the Manhattan School of Music, studying under Reiko Füting and David Adamcyk. Her work spans solo, chamber, opera, music theater, electronic, multimedia, and installation art, and has been performed by distinguished ensembles such as the Jack Quartet, PHACE Ensemble, Windscape, and ICE worldwide.

Published by: Josh Tatunay