By: James Manley

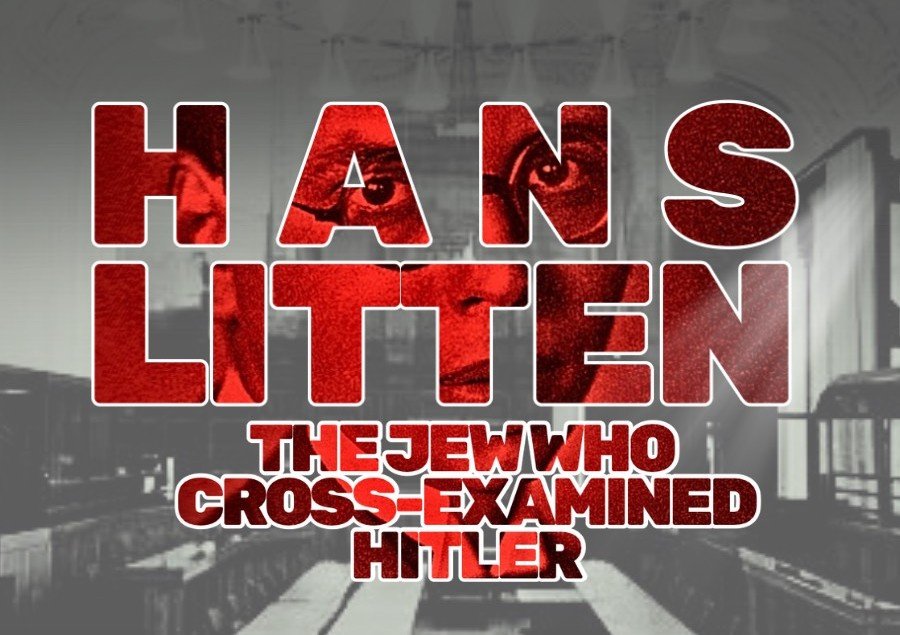

The lights rise on a Berlin courtroom in 1931. The air is tense, crowded with journalists, lawyers, and political agitators. At the center of the room stands a young Jewish attorney, precise and unflinching, as he calls an unexpected witness to the stand. Adolf Hitler, still two years away from becoming chancellor, is sworn in under oath. What follows is one of the most audacious legal confrontations of the twentieth century, a moment when the machinery of democracy briefly forced a future dictator to answer for his movement’s embrace of violence. This is the opening gambit of Hans Litten: The Jew Who Cross-Examined Hitler, the world premiere now arriving at Theatre Row.

When we spoke with playwright Douglas Lackey and director Alexander Harrington, both were clear that this play is not an exercise in historical nostalgia. It is an act of urgency. The production revisits a moment when the warning signs were visible, documented, and argued over in public, yet ultimately ignored. For contemporary audiences living amid political polarization and institutional strain, the story lands with unsettling familiarity.

“It’s a story of great heroism, and very little known,” Lackey said. A philosopher by profession and longtime professor at Baruch College and the CUNY Graduate Center, Lackey has spent decades translating complex ideas into accessible language. Writing this play, he explained, required the same discipline. “In both teaching and theater, you have to make ideas understandable, exciting, and relevant.”

Litten was not a radical. He believed deeply in the rule of law, in reasoned argument, and in the power of cross-examination to expose truth. His decision to subpoena Hitler was rooted in faith that democratic institutions could still hold extremists accountable. That belief, Lackey argues, is precisely what makes Litten such a compelling tragic figure. “The story of Hans Litten is a stunning tragedy,” he said. “I don’t want the audience thinking. I want them crawling out on their hands and knees. Aristotle had it right. The goal of tragedy is pity and terror.”

Photo Courtesy: Philosophy Productions

Perhaps the play’s most chilling insight comes not from Hitler himself, but from those who believed they could manage him. In the script, Litten’s father, Friedrich, argues that appointing Hitler to power is the best way to control him. It is a rationale Harrington finds painfully contemporary. The danger, the play suggests, is not only extremism but also complacency among those who believe systems will automatically restrain it.

Despite its subject matter, Hans Litten is not relentlessly bleak. The early scenes crackle with verbal sparring between Hans, his parents, and his law partner. There is humor, wit, and even music. In one memorable sequence, Hans and his colleague encounter Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill in a beer hall, where Weill’s “Alabama Song” erupts into the evening. “Music is essential to Doug’s plays,” Harrington explained. “Later, singing becomes an act of defiance.” The joy of art and culture stands in stark contrast to the brutality that follows, making the descent all the more devastating.

Staging a story that moves from courtrooms to concentration camps requires clarity rather than spectacle. Harrington and scenic designer Alex Roe have created a flexible set with multiple playing areas that allows scenes to shift without interruption. “In the first seven scenes, there are three locations and no set changes,” Harrington said. Costumes by Anthony Paul Cavaretta ground the play firmly in its period, while lighting by Alexander Bartenieff shapes the emotional landscape without overwhelming it.

For Lackey, the play is also a statement of artistic intent. “I’m tired of plays about jumbled identities and dysfunctional families,” he said. “Ideas are more interesting. History is more interesting. I want smart characters dedicated to a stable set of values.” Those values are embodied in Litten’s unexpected tenderness. One of the playwright’s great discoveries was Litten’s devotion to poetry. “He recited Rilke poems to concentration camp inmates,” Lackey said. “His dedication to art and literature has an almost religious intensity.”

The long-standing collaboration between Lackey and Harrington, now on its sixth play together, allows that complexity to breathe. “It’s a division of labor,” Lackey joked. “I do words. Alex does the stage.” Harrington, who began acting professionally at age ten and has directed since 1992, embraces his role as translator. “Doug is a man of ideas,” he said. “I’m the practitioner who puts those ideas on stage.”

What both men hope audiences leave with is not comfort, but resolve. “We are in a time that requires heroism,” Harrington said. “I hope the audience leaves inspired by Hans Litten and galvanized to continue the fight for democracy.” The play’s warning is clear. Democracies rarely collapse without notice. They erode while people debate, delay, and assume there will be time later.

Hans Litten: The Jew Who Cross-Examined Hitler begins performances January 30 and runs through February 22, 2026, with opening night on February 5, at Theatre Row, 410 West 42nd Street. Performances are Wednesday through Saturday at 7 PM, with matinees Saturday at 2 PM and Sunday at 3 PM.

The cast features Daniel Yaiullo as Hans Litten, with Stan Buturla, Zack Calhoon, Robert Ierardi, Whit K. Lee, Barbara McCulloh, Dave Stishan, Marco Torriani, and Mark Eugene Vaughn.

Tickets are available at hanslittenplay.com, by phone at 212 714 2442, or at the Theatre Row Box Office.

History does not only ask to be remembered. Sometimes it asks to be recognized in time.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article reflect the subject matter and themes of the play Hans Litten: The Jew Who Cross-Examined Hitler and are intended for informational purposes. Any political comparisons made in the article are drawn from the historical context presented within the production and are not meant to endorse or criticize any specific political figure, party, or ideology.